“We sail, we sail, in sun, rain, or hail;

The world is beneath us, the clouds mark our trail!”

The Ship Agency’s ditty was the soundtrack of progress. An operatic male voice, opening triumphant! A clarion woman, eagerly echoing! The tinny horns accompanying them, heralds of the future!

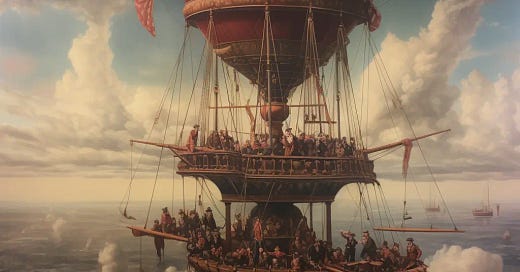

Balloons lifted aeroships. The Ship Agency’s aeroships lifted the world into a new age of travel. The Ship Agency’s ditty lifted the heart.

Hawkers whistled it. Gramophones blared it. Buskers enlivened their sets with it.

Beth Lewin’s memories drowned in it.

Corrupted by bitterness, Beth thought the whole thing rather sinister. Balloons and hail did not mix. The exorbitant fares charged for passage certainly suggested that most of the world was beneath the Ship Agency’s notice.

And anyway, the ditty was plagiarized.

She swallowed a sour expression, straightened her new uniform, and boarded the aeroship attached to the dock. The child inside her, who once would have stabbed someone with a hatpin for a chance to fly, was quiet. No amazement, no gratitude, no spark of adventure.

“Tickets! Have your tickets at the ready, ladies and gentlemen!”

She played her conductor role with a tight smile and tighter bun. The customers surged toward this young woman in a smart jacket and pleated wool skirt with official gold trim.

Their eyes were bright. The children skipped with excitement. The women carried wicker picnic baskets.

But for the caprice of man, thought Beth, go I.

She set aside her distaste. She had, after all, sold her time and self-worth to the Ship Agency for four dollars a day.

“Welcome, madam, the top deck stairs are to the right! Thank you, sir, if you’ll go left and forward toward the lower deck …”

Each obeyed with a grin, certain there were no bad seats on this aeroship. A coifed lady at the Ship Agency had sold them tickets, the lower deck for economical travelers, the top deck for society’s better sort. She had sold both as unparalleled luxury.

And considering it was but a four-hour journey through marbled skies against a two-day trip by cramped, sea-tossed boat, the lady had not lied.

Once all tickets were collected in her satchel, Beth hurried up the gangway. Her disgust rose like bile when she saw the top deck as crowded as the bottom. The seat cushions were nicer, that was true. And a steward was distributing liqueur in glass tulips with the pomp of a fine-dining waiter.

But Beth didn’t think the six-dollar difference between the two decks was worth it, not for four hours.

The gates closed. Orders were given. The furnace hummed to life, the tangled lines straightened, the balloon lifted, and they were off.

Beth peered over the railing despite herself. From above, the city admitted its youth: the streets were a grid, the center denser, the buildings along the radial arms lower and spread. The river cut through, itself bifurcated with decorated bridges.

Forewarned was forearmed, so Beth didn’t join the passengers in their gasps and coos.

“It all seems rather empty after a moment, don’t you think?”

Startled, Beth looked sideways and saw the steward beside her, his tray tucked under one arm. He gazed at city and cloud castles alike with the dispassion of a sated lizard. He was an older man, and likely had earned his world-weariness the usual way.

“Without the dragons, yes, quite empty,” she replied.

“It was either we fly or they do,” cautioned the steward, mimicking the official line.

Beth knew that. The dragons had believed the sky belonged to them alone. They would carry no passengers but their partners.

Beth would never be a Sky Agency courier like her father. She would never lash herself and a bag of mail to a great beast, with no safeguards but worn rope, her wits, and trust in her winged partner.

Besides, the dragons had owned something the balloon-makers needed. And so, ten years ago, the government had dissolved the Sky Agency so that the Ship Agency might usher in progress.

But progress had come too late for Beth’s father.

Mr. Lewin had died doing what he’d loved, the Sky Agency representative had said at his funeral. That had been scarce comfort to his widow and orphan.

Aeroships were safe. They were the future. Mrs. Lewin was grateful that innovation had prevented daughter from following father. And now that her daughter was earning four dollars a day, she was grateful indeed. Mrs. Lewin aspired to be a top-deck kind of woman.

The steward must have noticed the ambivalence on Beth’s face, because he motioned toward the balloon. It was red, thick, leathery, covered in iridescent scales that glistened like an oil puddle.

He said, kindly, helpfully, “In a way, they’re still flying.”

He rambled on, but Beth couldn’t hear him. Now that they were sailing straight and high, the pilot flipped a switch and the gramophones barked to life.

A memory drowned out the Ship Agency’s ditty. It was of her father at the dinner table after he’d return each Saturday, bearing his weekly dollar and the agency’s grateful handshake. He’d sip some milk and, laughing, croon the Sky Agency’s ditty:

“We fly, we fly, across the endless sky;

Our bags filled with wishes, our spirits soar high!”